This year has been one filled with a lot of learning about the process of reading, how children learn to read, and the knowledge of how to teach reading with the use of any good reading program. I’ve already shared a bit about my experiences at The Reading League’s National Conference, as well as items I’ve learned as part of our experience as members of Cohort 2 of the Indiana Reading Cadre. Currently, I am one of several members of the team in my building engaged in Lexia LETRS Professional Learning. In today’s post, I want to share with you one of my key takeaways from the first unit of LETRS.

First of all, what is LETRS? LETRS stands for Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling. It’s a professional development course of study for instructors of reading, spelling, and related language skills. Its goal is to take current research on reading instruction and bridge the gap to classroom practices that allow teachers to feel confident in their instruction.

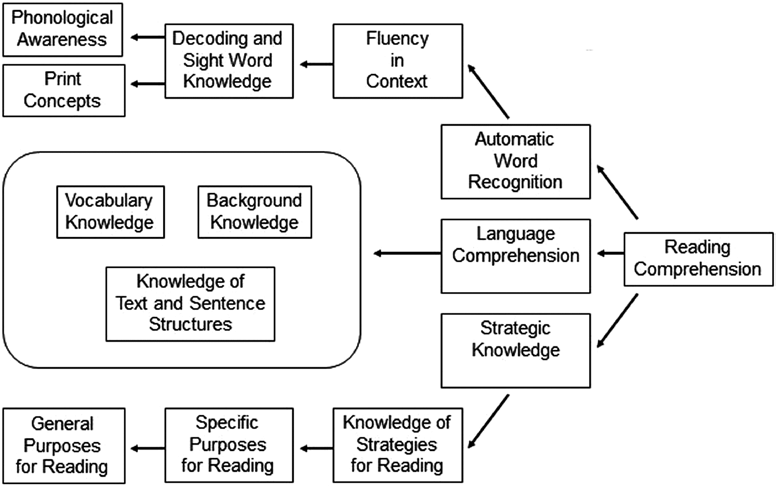

Unit 1 covers a variety of topics, and I would describe it as something of an introduction to the learning that will be happening throughout the remaining seven units. For me, the most impactful section was on the topic of how children learn to read and spell. One piece of the key takeaways is that for students to develop the skills necessary to be skilled readers, we must teach them deliberately. As I’ve shared before, in previous posts (check out my previous posts on the purpose of reading) the ultimate goal of reading is to comprehend. In a skilled reader, that seems to be somewhat automatic. Their knowledge of word recognition skills combined with their language comprehension makes it seem as though reading is an automatic process. Recent science tells us that’s not true – with the development of eye-tracking software, we know that the human eye of a skilled reader will scan an entire word in 250 milliseconds (that’s a quarter of a second!).

The research of Linnea Ehri does a great job of helping to define the stages of reading development. To learn more about the typical development of reading, check out this post from Reading Rockets here. As teachers of reading, we want to move our students to a consolidated reading practice. For most kids, this happens sometime in 2nd or 3rd grade. Often, as students are moving towards the consolidated phase of reading, and truly skilled reading, we are concerned with their reading rate, or words correct per minute. When students do not become fluent readers, it has a great impact on their ability to comprehend.

One thing that I see at times when talking with teachers of struggling readers is a focus on their inability to comprehend their reading. But what is important to remember is that most of the time when a student struggles with comprehension, there is some underdeveloped skill that must be in place to get to strong reading comprehension. Instead of using interventions to support a student’s reading comprehension, we have to identify the gaps. Is there an issue with their phonological awareness or phonics skills that impact their comprehension? Or does the student lack key vocabulary? Or could there be a lack of background knowledge in the reading topics?

To help us understand where a student is in their reading progression, tools like The Cognitive Model of Reading Assessment (see below, created by Michael McKenna and Katherine Stahl) is a great tool to think of the skills that build solid reading comprehension. I like to think of the skills as building on one another. If I have a student who is struggling with reading fluency, then The Cognitive Model reminds me that maybe the underdeveloped skill is actually in decoding and sight word knowledge. This would impact the type of intervention I might want to use for a student, as well as what my progress monitoring tool might be. If I want to identify more specific needs, I might use a diagnostic tool such as the Phonological Awareness Screening Test (PAST) or some form of a letter naming and word reading survey (LETRS has one included in their assessment resources).

Ultimately, we need to remember that the thing we think is the issue is not always the issue. Often, there are underdeveloped skills that come earlier in the progression of reading skills that will lead to the struggles that we see right now.

Think about a student in your class. What is the thing that they seem to be struggling with? Take a look at the cognitive model, and think about the areas that come earlier. Could you do a quick formative assessment on that skill to see if there actually are gaps there that are impacting the reading comprehension? If so, you need to take a step back on the progression. Share with us what you are thinking about as you reflect on the students you serve. Share with us how it might impact your next steps with that child.