Have you ever had moments in your life where something seemed to be coming at you from multiple directions? That’s how I learned about my all-time favorite television show: Breaking Bad. Numerous friends from different backgrounds talked about it sometime during the second season, and I decided to give it a chance. I was hooked. That’s also how I came across the book Game of Thrones. I knew the books before they were ever a series on HBO, but again, several people who knew me recommended them to me, so I gave it a shot, and I was hooked.

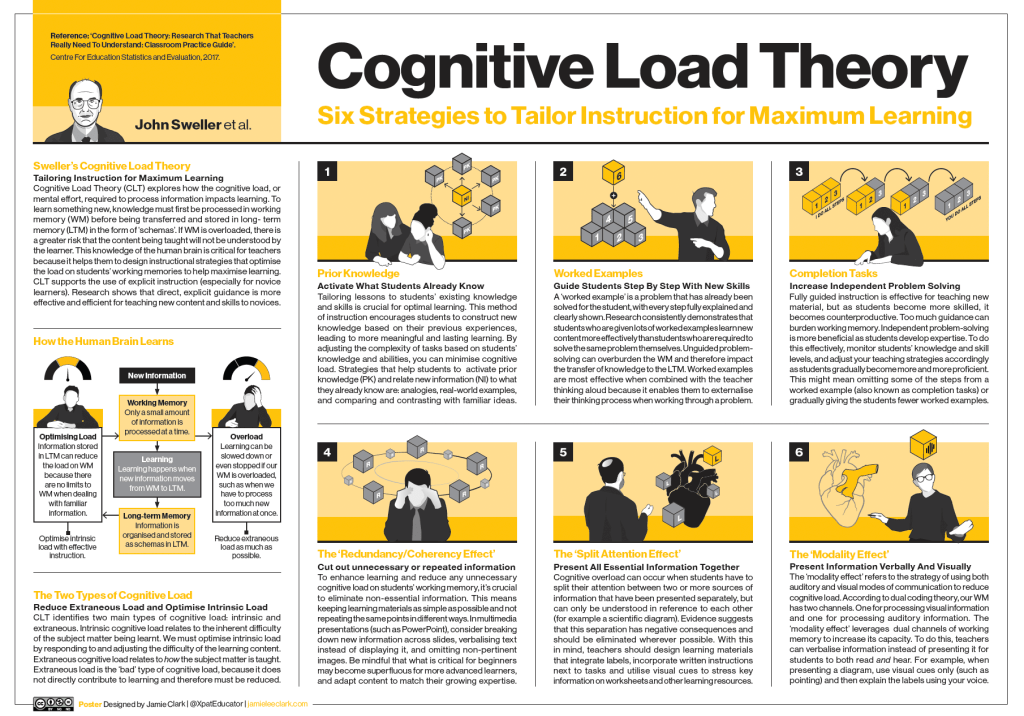

That’s kind of what happened over break with Cognitive Load Theory. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not a new topic to me; it’s something I’ve heard of and am aware of, but I’m not sure that it was something I could have explained well or taught to someone else. But over break, I was scrolling through social media with my feet propped up on the couch. During an afternoon, I saw references to John Sweller and Cognitive Load Theory from several different people I follow who are not connected in any way other than being educators. Their posts led me to a couple of articles, a fantastic graphic that I’ll share below, and a podcast that I’ll also share below. However, the post that stood out the most to me was the quote below from Dylan Wiliam. It made me stop what I was doing and really take note:

I mean, when the guy who’s known for introducing the concept of “assessment for learning” says that something is the single most important thing for teachers to know, it gives me pause. So, while it was a break, and I know I encourage you all to take a break, I always find ways to fill at least a little of my break with learning. Let me share some of it with you.

So, first of all, let’s get a working definition: Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) explores how the cognitive load, or mental effort required to process information, impacts learning. According to Jamie Clark (@XpatEducator), “To learn something new, knowledge must first be processed in working memory (WM) before being transferred and stored in long-term memory (LTM) in the form of ‘schemas.’ If WM is overloaded, there is a greater risk that the content being taught will not be understood by the learner.”

So imagine that our brain has something like a “mental backpack” with limited space to carry things. CLT helps us determine how to pack that backpack best so you (or your students) don’t get overwhelmed. This is particularly important to remember in elementary schools because students’ working memory capacity is still developing.

So, let’s talk about the different types of cognitive load. There are three main types:

- Intrinsic Load: This is the inherent difficulty of the material. For example, learning to add single-digit numbers has a lower intrinsic load than multi-digit subtraction with regrouping. Higher intrinsic loads are unavoidable at times, but we make them manageable by breaking them into smaller chunks and using scaffolding to support learning.

- Extraneous Load: This is an unnecessary mental effort caused by how information is presented. For example, overly busy worksheets, changing the directions on each assignment, or giving verbal instructions while students are focused on reading can create distractions. Reducing extraneous load frees up mental space for actual learning. This makes me think of the book EduProtocol Field Guide by Marlena Hebern & Jon Corippo. They utilize a concept of learning frames or protocols that any curriculum can be plugged into to make the content engaging and more accessible for learners.

- Germane Load: This is the productive effort students use to connect and organize new information into meaningful patterns. Activities like practicing or applying knowledge creatively (especially after a solid understanding of the foundational skills) increase germane load and lead to deeper learning.

OK, now that we understand what CLT is and the different types of load that impact learning in our classroom, the next question is, what do we do to support our students? Well, we must understand that working memory in students, especially young ones, is limited. Most learners can juggle only 4-5 pieces of information at once. But for some of our students, even that would be a stretch. There are a few things we can do to support learning in our classroom:

- Simplify and scaffold: Break your lesson into small steps and introduce each concept individually. Then, gradually, increase the complexity. Go through the “I do, We do, You do” cycle with each level of complexity. This builds mastery in each of the steps. For example, when teaching place value, ensure your students understand the tens and ones place entirely before moving on to the hundreds place.

- Use visual aids: Pictures, charts, and diagrams help offload some mental work from working memory to the visual system. Anytime you can add a visual, it will support your students’ working memory.

- Provide clear instructions: Give concise, step-by-step directions and check for understanding before moving on. It’s good practice to plan your directions so you can be sure they are clear and concise. We are all tempted to sometimes give directions while students are in the middle of something. Most students will not hear or process the direction you just gave.

The next thing we want to consider is to minimize the extraneous load. Remember, this is the unnecessary mental effort that can sometimes be caused by how information is presented.

- Declutter your teaching materials: Try to avoid overly decorative slides, worksheets, and visuals, and take a moment even to scan your classroom walls. Too much visual stimulation creates mental noise that can add to a student’s cognitive load. I know that sometimes we like things to look pretty and cute, and those motivational posters are fantastic, but too much is a form of distraction. Try to stick to the essentials that directly support the learning objectives or your current units and skills.

- Align instruction and tasks: If you’re explaining a concept, ensure your students are focused on listening and not distracted by writing or unrelated activities. Phrases like “Apples up,” “pencils down,” or “all eyes on me” can help keep students focused on your explanation and not some other task.

- Create quiet and well-lit learning environments: Minimize background noise and distractions, especially during independent work time. Low lighting can have a calming effect at moments, but during work time, low light can increase cognitive load because it is difficult to read text on a page when there isn’t enough light. That is why there are state laws and standards about the possible light levels within a learning space (hence the new lighting installed not that long ago).

After thinking about the extraneous load, we want to optimize the germane load. Students use this productive effort to connect and organize new information into meaningful patterns. It’s about practicing and applying skills to create deeper learning. Things we might do to help with this optimization include:

- Connect to prior knowledge: Use your students’ knowledge to build a new understanding. For example, in math, you might review skip counting before leading into a lesson on multiplication. Or use experiences that your students may have had in their lives to help build background knowledge before reading a story.

- Encourage reflection: Take time for students to reflect on their learning. This could be in a whole class setting, in a think, pair, share, or even in a journaling activity. Prompts like “What did you notice?” or “Can you explain this in your own words?” help to deepen understanding. Some other reflection questions might include “What is one thing you learned today that you didn’t know before?” or “What was the most important thing we talked about today? Why?” or “What part of today’s lesson felt easiest for you? What felt hardest?” There are a ton more potential questions that could be used for reflection, including ways to connect to prior knowledge (how does this connect to something we learned earlier?), evaluating effort and strategy (was there a step that you found tricky? how did you figure it out?), highlighting growth (what made you feel proud about yourself today?), encouraging curiosity (what is one thing you’re still wondering about?), building social and emotional awareness (how did you feel during this activity? why?), or looking ahead (what do you think we might learn next?).

- Practice, practice, practice: Repetition solidifies learning, but it needs to be varied to maintain engagement. Maybe you start with direct instruction, then some practice on whiteboards that students hold up for you to check, and then you could move into some partner or small-group work. Maybe there could be some flashcards, or the skill could be practiced in some game format. By varying the format, you ensure that students have plenty of opportunities to practice the skill and solidify learning, but those opportunities are varied enough that they can maintain engagement.

So, let’s discuss some age-appropriate supports. Obviously, each child has different needs, but in general, there are some developmentally expected abilities in terms of CLT based on a child’s age range.

In primary grades (K-1), we want to use concrete, hands-on materials as much as possible. At this age, students are still developing their abstract thinking skills, and manipulatives provide tangible ways to explore concepts.

As you plan lessons, think about how and where you can add hands-on materials to any lesson. This might include counting bears, unifix cubes, pattern blocks, playdough, counters, letter tiles, and magnetic letters. These objects allow students to manipulate a concrete object to support their thinking and reduce their cognitive load. Next, we want to keep activities short and focused. The attention spans of 5 and 6 year olds may only last 5-10 minutes, so a mini-lesson may only be 5-7 minutes, followed by a hands-on activity of about 10 minutes, and then ending with a quick share out or reflection of 3-5 minutes. Whenever possible, incorporate play-based learning. I had a professor at IU who must have used the phrase “learning is social” a million times in my classes with her. Young children naturally learn through exploration and play. It keeps them engaged while reinforcing skills. You might use role-playing games to practice social skills or set up themed learning opportunities, like the “grocery store” for math or a provocation for a writing station in literacy. Young students also thrive on routines and predictability (let’s be honest, I do, too!). Having predictable routines helps reduce anxiety and allows students to focus on learning. Things like a visual schedule, consistent transition signals, and a routine for the beginning and close of the day help reduce cognitive load because students will know what to expect and when to expect it.

In the upper elementary grades, students develop greater independence, cognitive abilities, and social-emotional needs. However, they still thrive with a certain level of structure and engagement. So, let’s consider a few ways we can support our upper elementary (2-4) students.

One of the first and most important ways to support students with their cognitive abilities is to encourage active participation. Students at this age can participate in discussions and collaborative activities, which deepen their understanding. You can do this through think-pair-share activities that help engage all students in discussion or incorporate hands-on projects. Another way to involve students in classroom participation that may not always seem like a direct connection is through classroom jobs or leadership roles, which help students feel responsible. We also want to promote critical thinking in our students. They are ready to analyze, compare, and apply rather than memorize facts. Open-ended questions that require reasoning push students to use critical thinking skills, such as “Why do you think that happened?” or “What would you have done differently?” Scaffolding and gradual release will also help build independence in our upper elementary students. Things like modeling a skill (writing a strong topic sentence, for example), guided practice side-by-side either individually or in a small group through a problem as students try it themselves, and then independent practice where students try things on their own, gradually increasing the complexity as they gain confidence are all ways to support students growth in independence.

Upper elementary students also need a lot of help to develop executive functioning skills. Directly teaching organizational strategies, like using planners to keep track of materials, assignments, projects, or take-home/bring-back folders, will help. Teaching students how to take an enormous task and break it into smaller steps helps them learn about creating checklists or understanding the steps needed to meet a goal. Things like timers and schedules can help students learn to manage transitions better and be able to focus on work during their in-class time.

As my readers know, most of my time and thinking is spent in the elementary realm, but I know that there are a few of you who read this who come from the middle and high school levels. I don’t know that I have direct recent experiences that I can give you, but I found what seemed like a great article from Edutopia with some concepts that seemed to apply much more to the secondary level. You can see that post here.

On the other hand, if you’re interested in this stuff and, like me, find understanding how the brain works absolutely fascinating, I found this Classroom Practice Guide from the New South Wales Government titled “Cognitive load theory in practice.” I did a scan, not a full read, but it seems like a great resource to learn more. You can find that here.

As with anything, our work in meeting the needs of our students means that we need to pay attention to signs of cognitive overload – things like frustration, disengagement, or difficulty recalling prior lessons. If students show signs of cognitive overload, it’s time to make some adjustments. Simplify, slow down, or provide additional support as needed. When you keep the concepts of cognitive load theory in mind, you set your students up for better opportunities for learning and growth. This will help them move towards proficiency, which allows them to meet the goals we have set as a school.

Finally, there are a couple of resources – first is kind of like a cheat sheet graphic that you could download and print to use as a guide. Maybe keep it near your planning materials as a reminder of how you can maximize and optimize learning in your classroom. The second is a great podcast that was shared with me that digs into CLT a little deeper in a conversational format if that is more your jam than reading!

Click on the Podcast logo above for a recent episode of the Critically Speaking podcast. This episode is about math education in particular, but it hits on concepts of cognitive load theory based on the work of John Sweller. This conversation between Terese Markow and Dr. Anna Stoske hits on a wide range of issues around a decline in math education and has some key takeaways that support direct instruction and the need for foundational skills to get to higher-level thinking.

2 thoughts on “Cognitive Load Theory”