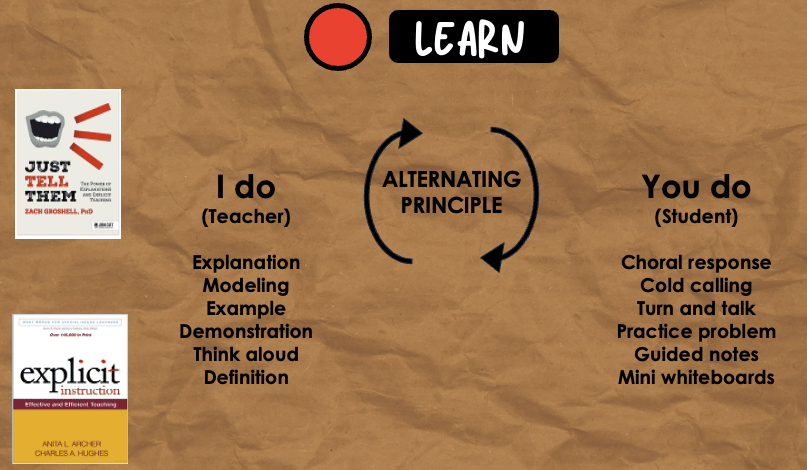

In a recent round of professional learning, we dug into what Zach Groshell calls the alternating principle, or the input/output cycle. Before that learning, we shared a chapter from the book Just Tell Them with our teachers. In that chapter, Groshell shares that “While students need guidance during knowledge acquisition, they can also become overloaded if presented with too much information at once.” This relates to the concepts of Cognitive Load Theory, which I’ve shared before.

Groshell goes on to share that effective explainers manage attention, behavior, and cognitive load by breaking their presentations down into smaller chunks. If you have watched any of the matches of the Australian Open, you know that in a tennis match, there is a quick back and forth between the two players. That’s how it should be during the early stages of learning a new skill. Groshell uses Direct Instruction programs as an example: when implemented successfully, students should respond at approximately 9-12 responses per minute.

The key takeaway here is that effective explanation is not about what you, as the teacher, can tell your students. It has more to do with the dialogue you build with your students. Teachers and students should take turns. There should be a brisk alternation between providing information and asking students to respond through formats such as choral response, turn-and-talk, and cold-calling.

Recently, I’ve been popping into classrooms to observe the input/output cycle informally. There are a few things I have noticed:

- In classrooms where the input/output cycle is 5 or more per minute, student engagement is higher. It’s that “Perky Pace” that we’ve learned about from Anita Archer in the past. More inputs and outputs per minute lead to greater academic engagement, which in turn increases learning.

- When there is more time between inputs (such as walking around to check each student’s answer on their whiteboard), students are less engaged and have more time to talk (remember the phrase from Archer – “Avoid the void, or they will fill it.”). To speed up that process, can you stand at the front and have students hold up their whiteboards? Then you can scan the answers and provide feedback more quickly, reducing the time between input and output.

Research shows that interspersing clear, concise teacher input with frequent student output is an important part of effective instruction (Pomerance et al., Learning about Learning, 2016). As you plan your lessons, make sure to include frequent inputs and outputs, and consider how you’ll have students share their work (choral response, cold call, turn-and-talk, mini whiteboard, etc.).

By implementing the alternating principle in your classroom, you can increase engagement, which in turn is linked to higher student learning. What is something you might try next week based on your learning here? Share your thoughts in the comments below.