As many of you know, my go-to strategy for professional development is typically through podcasts or reading, and often it’s a podcast that drives me to read something. One of the podcasts that I like to listen to is called Chalk and Talk. It is hosted by Anna Stokke, a mathematics professor at the University of Winnipeg in Winnipeg, Canada. While the topics can be wide-ranging, it typically comes back to math instruction. You can check out that podcast episode by clicking here.

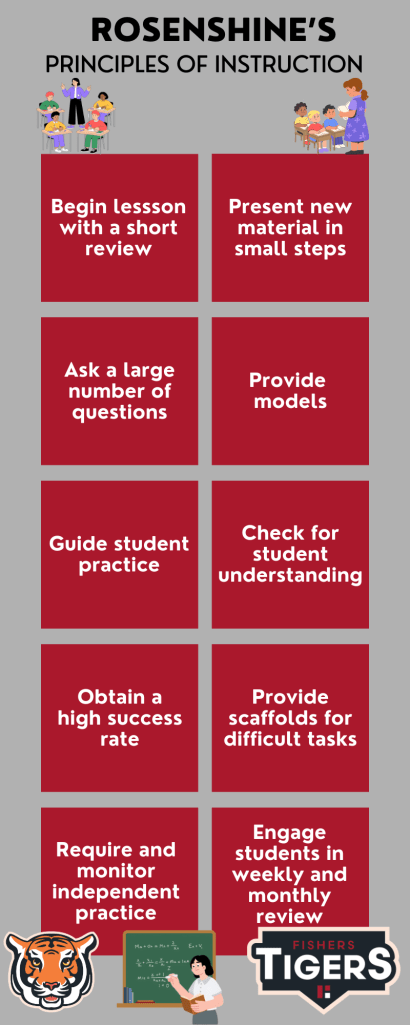

On this episode, Tom Sherrington, an education consultant, author of Rosenshine’s Principles in Action, co-author of the Teaching Walkthrough series, and a former teacher and school leader with over 30 years of experience, was there to talk about Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction. What struck me about this research is that it is directly related to our work on Explicit Instruction by Anita Archer.

Rosenshine’s Principles serve as an excellent guide to evidence-based teaching. You can read the piece that Rosenshine wrote by clicking here. I’m going to try to distill that 9-page article into something a little more digestible.

Just for some background, Barak Rosenshine was a teacher and educational researcher, and his principles are described as a bridge between educational research and classroom practices. Rosenshine created the principles based on his work with three sources: 1) research in cognitive science, 2) research on master teachers, and 3) research on cognitive supports. If you’d like to know more about each of these areas, check out the first page of the article linked above.

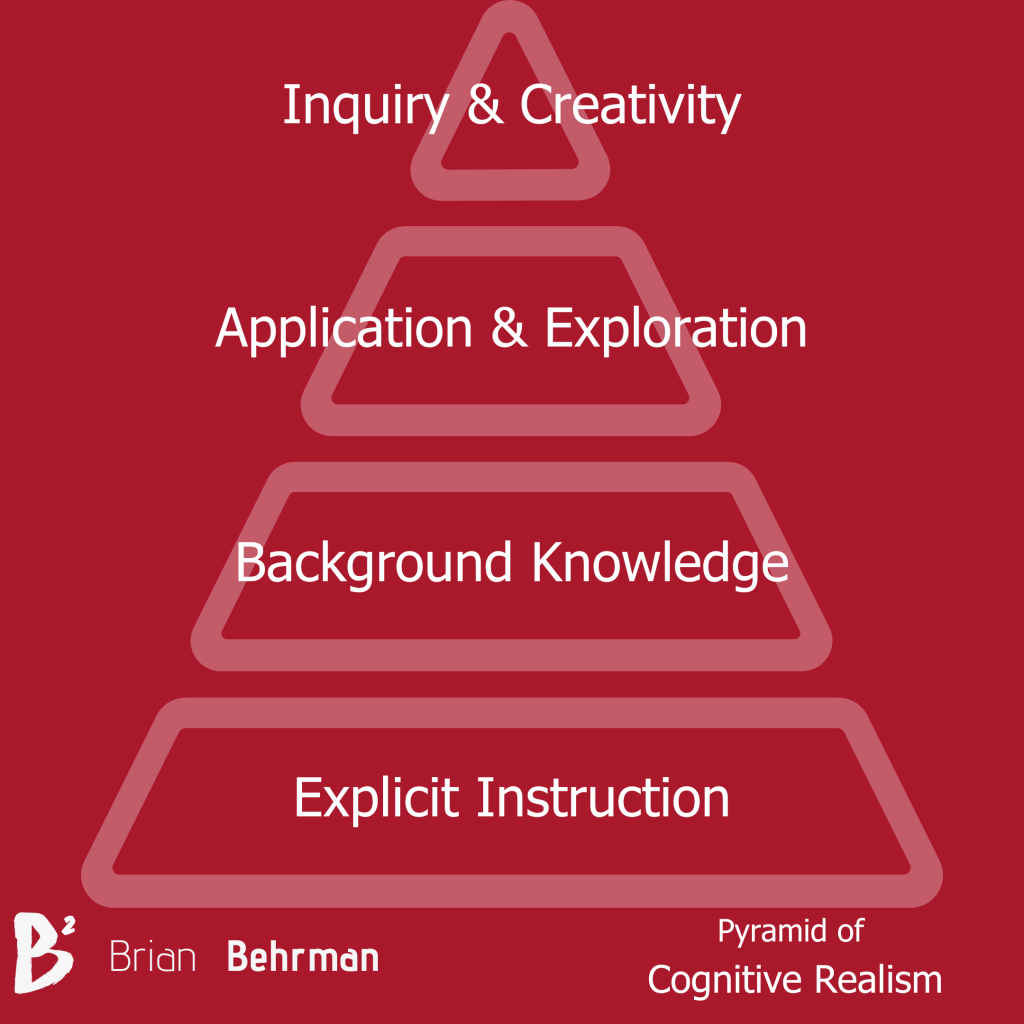

As I’ve shared before, education is ultimately about moving a novice towards mastery by building strong background knowledge. Below, I’ll share a bit about the first 5 of the 10 principles from Rosenshine’s research. Implementing each of these principles consistently should lead to higher mastery rates for our students.

1) Begin a lesson with a short review: Cognitive science tells us that one of the most successful ways to solidify learning is through retrieval practice. This means generating answers to questions. By asking students to answer questions about a previous lesson, you create additional retrieval practice, which leads to automaticity. In math, this might mean beginning a lesson by reviewing a few questions students got wrong during independent practice or homework. In ELA, it might include a daily review of key vocabulary words. Rosenshine’s research supports 5 to 8 minutes each day to review previously covered material and create some retrieval practice opportunities.

But the review at the beginning of the lesson was not limited just to things done yesterday. It would also include a review of the prerequisite skills for the lesson that is planned for today. If we don’t take the moment to review, those neural pathways may not fire as quickly as we’d like, increasing the cognitive load for students.

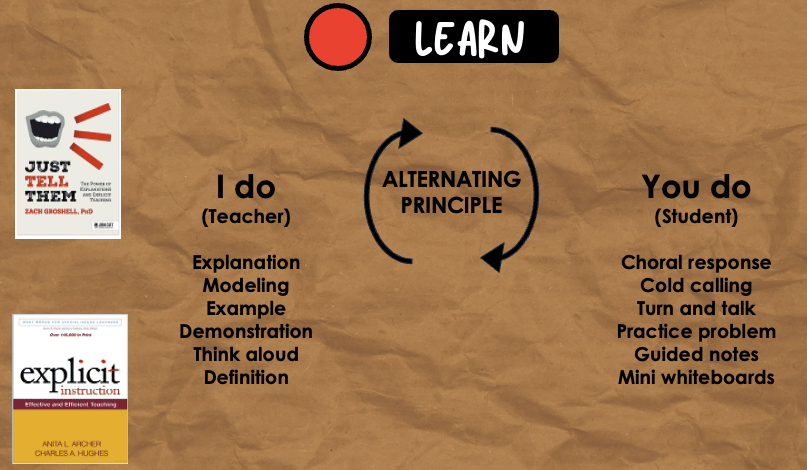

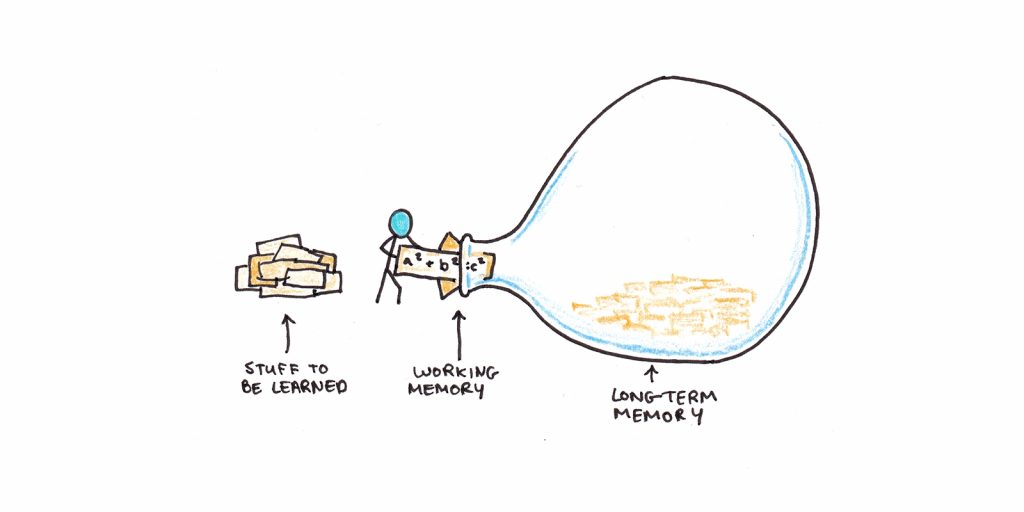

2) Present new material in small steps with student practice after each step: Too often in teaching, we will teach our whole lesson, which may ask students to accomplish multiple new skills, before any chance at practice. A student’s working memory cannot hold all that information at once, and we will invariably forget some of what we learned at the beginning of the lesson when it’s time for independent practice. Effective teachers recognize this, model the skill, do some guided practice, and then include a little bit of independent practice multiple times within one lesson. This means teachers may have to spend more time moving between modeling, guided practice, and independent practice.

In an ELA classroom, while working on summarizing a paragraph, an effective teacher might model identifying the paragraph’s topic in a think-aloud. Then, there might be guided practice using structured questioning to identify the topic in new paragraphs. Then students would work independently to identify the topic of at least one paragraph. Once practiced, the same gradual release could be used to identify the main idea, and finally, we’d gradually release, identifying the supporting details in paragraphs. Finally, students would practice putting it all together, the topic, main idea, and supporting details, from yet another paragraph. The cycling back and forth between different skills reduces cognitive load.

3) Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of ALL students: Questions force that retrieval practice mentioned earlier. Expecting all students to answer increases the amount of practice for each student, and seeing answers lets you know whether some, most, or all kids know the skill. If we aren’t at a minimum of 80% mastery, we aren’t ready for a new skill yet! Follow-up questions that ask students to explain how they found the answer further strengthen process learning, as opposed to the teacher repeating the steps. This means fewer questions that require just one student to share an answer. When we do that, some students can choose to opt out.

In practice in the classroom, we can increase chances for students to respond and decrease chances for students to opt out by:

- Using a turn and talk

- Written 1-2 sentence summary to share with a neighbor

- Repeat the procedures to a neighbor (have both partners do this!)

- Raise your hands if you know it (quick check of who knows)

- Dry-erase board to show an answer

- Raise their hand if they agree/disagree with the answer given

- Choral response

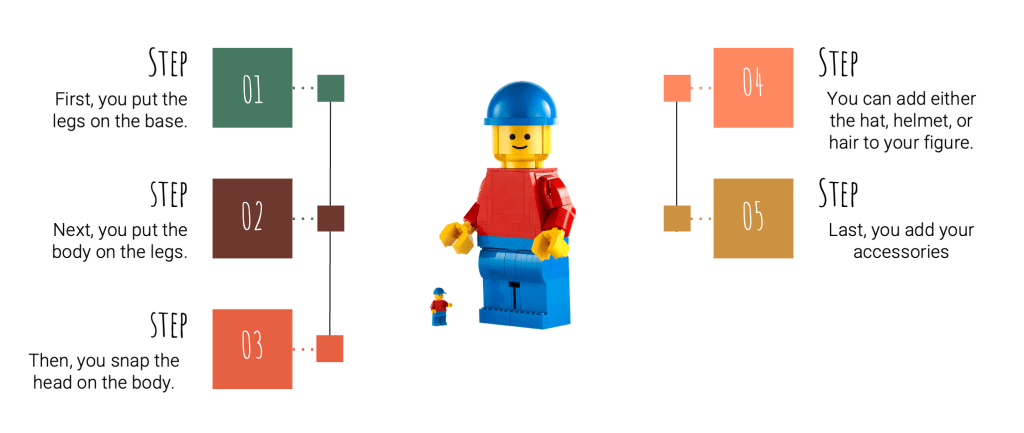

4) Provide models: Models and worked examples help students learn the process to solve problems correctly. This happens during the “I do” portion of a lesson. When we have novice learners, we need to just tell them what to do the first time. Too often, teachers seem to jump to “What do you think we should do here?” on the first problem given. This allows incorrect answers and is not a question that guides students to success.

As you move into the “we do” portion of a lesson, in math, you might use worked examples, but ask students to complete the last step, then the last 2 steps, and so forth until they seem to have reached mastery. In reading or writing, this might look like the teacher modeling a skill, then doing the same skill a couple of times together, and finally having students do the thing independently.

Fundamentally, the process to think about is start with a question/prompt, model what to do, use guided practice through a similar prompt/question, and then supervise independent practice with clear academic feedback on the skills.

5) Guide student practice: Successful teachers spend more time guiding student practice of new material. Many of you know that I spent time coaching both basketball and football. During practice, if we were learning a new play, we would start by running it “against air” (no opponent) so my players would know what to do. Once we were consistently doing the right thing without an opponent, I would add a defense to run the play against, but we’d walk through the play a few steps at a time. Then we’d run the play at half speed. Finally, we’d get to the point of running the play at full speed against an opponent. What might that look like in the classroom with an academic skill?

As a teacher, you can facilitate the practice by asking questions directly related to the steps of the new skill. In math, this might mean going over more examples with explanations, using check-for-understanding questions along the way, and then just a few targeted independent practice problems. If students are still having problems with the independent problems, then we go back to some more guided practice. In general, when students have seen more examples, they are better prepared and more engaged in independent work time.

The principles that we put into place as teachers can help create learning environments that reduce cognitive load and increase a student’s ability to reach mastery. Rosenshine’s research indicates that master teachers who achieved successful student learning outcomes were more likely to consistently implement these principles. So, as you reflect on the five principles above, are there things you feel like you do well? Are there areas where you feel that you could improve? I suggest picking one and setting a goal to implement it consistently in your classroom. The more you plan for a new thing, the more natural it becomes to do it without thought