In December 2009, I decided to sign up for a Twitter account. Some of my friends were talking about it, and at that time I was noticing more places would share their Twitter handle on advertisements. Like most people, after signing up, I started following people or accounts I was interested in. On that list, I added friends, some favorite athletes, a few news sources, and people from pop culture. In the beginning, I was mostly a “lurker.” I followed conversations, but never posted or replied. I would log in from time to time, but it wasn’t something that I utilized on a regular basis.

About three years later, I was driving to school when I heard an interview that gave me a fresh perspective on the potential uses of social media as an educator. On Morning Edition on NPR, I heard Scott Rocco talking about this weekly Twitter chat called #satchat. Scott and Brad Currie, another superintendent in New Jersey, co-founded #satchat as a chance to have a discussion on important topics in education through social media channels so that more people could be involved. At the time of the interview, there were about 200 people that participated in this weekly chat.

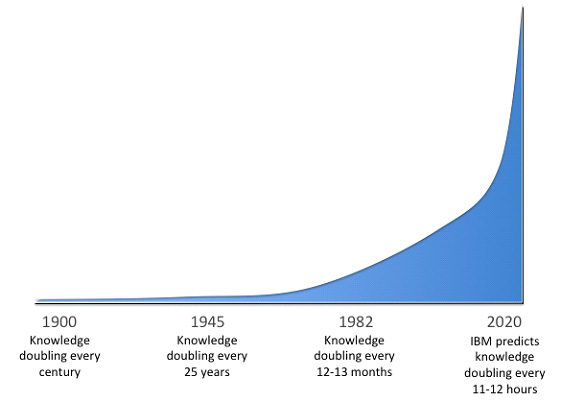

It was the fall of 2012. I was a classroom teacher at the time. In addition to my teaching responsibilities, I was coaching junior high football and basketball and had 2 young children at home. I was busy! I knew that I wanted to continue to grow as an educator, but I didn’t necessarily have the time for book studies and conferences. I needed something that could be a little more on my own schedule. Hearing about #satchat let me know that maybe there was another way for me to learn that could be on my own time. That radio program taught me that an app on my phone could connect me with educators and emerging leaders in education from all over the world.

Soon after I participated in my first ever #satchat. I don’t recall the specific topic, but I did start following several of the other educators that were active in the chat. Since then, I have looked at Twitter as my own Personal Learning Network. While I still use social media for a variety of purposes (I still follow athletes and pop culture icons, and it’s often the first place I look for news on just about any topic), it is also my go-to resource for growing as an educator and leader.

This belief about social media was only reaffirmed as I listened to Matt Miller at Ditch that Convention in 2017. I don’t want to steal his story, and some of you may be aware of who Matt is. During the keynote, he said:

Matt was the lone Spanish teacher at a small rural school in western Indiana. As the only teacher of his subject in his school, he felt that he struggled to create meaningful learning opportunities for his students. Eventually, he found a Professional Learning Network through Twitter and realized there were many more possibilities for his students. His learning through Twitter led him to begin presenting to countless educators, writing multiple books, hosting podcasts, and more. Without those connections created through Twitter, he felt he might have burnt out, and eventually left education.

So, here’s my suggestion to all of you reading this – If you aren’t on social media to learn as an educator, start making use. Twitter is still my go-to source for learning from others and sharing about amazing things happening in my own school and world, although others prefer to use Instagram, Facebook, or even TikTok. If you follow me, you’ll see posts about things happening in my school and district, but I also share pieces of my personal life as well. I like to be able to be my full self.

If you are new to using social media as an educator, seek out people in positions like you. When I moved into my current role, I began following as many elementary principals as I could. Next, learn to use hashtags! Some of the ones I check in on regularly still include #satchat on Saturday mornings, but I also like to look at #echat, #edleadership, #PLCatWork, and #TLAP. As you check out those hashtags, start following anyone that is posting things you are interested in, or would like to learn more from.

As an educator, I believe strongly in the importance of lifelong learning. While there are lots of different ways that we can learn, one of the greatest sources for me in the past 10 years has been through social media. The portability of my phone allows me access to the world no matter where I am or what I’m doing. If you’re new to the world or social media in education, feel free to seek me out. I’m @brian_behrman on both Twitter and Instagram.

Now, go on and build your own Personal Learning Network!