Recently I have been spending a lot of time thinking about the power of learning in the school setting – not just for students, but also for the teachers and staff of our school. In turn, that has led me to look into the history of public schools in the US. As a quick refresher, American public schools were originally organized according to the concepts and principles of the factory model of learning. Around the late nineteenth century, effort had been put into the creation of school in the image of a factory. One of the books that exemplified this was Frederick Winslow Taylor’s book Principles of Scientific Management. Taylor argued that “one best system” could solve any organizational problem. In this theory, it was the job of a manager to identify the best way, then train workers to do so. This hierarchical, top-down management created a rigid sense of time and accountability. This process is best modeled by the assembly line that existed in factories of the time. The advantage of an assembly line is that the parts that made up the assembly line were viewed as interchangeable. Any worker could complete any role with the appropriate training. Business leaders and politicians argued that schools should adopt a similar model to produce the kinds of workers that were needed in industry.

Now, I see a lot that is problematic in this quick overview above. First, “one best system?” Does that ever exist anywhere? I think if we looked at factories and assembly lines of today, we would find them to be vastly different from the version of the early 1900s. Innovation has changed the process. Schools need to keep up with those changes. Next, do schools exist in a hierarchical, top-down model? I mean, they may exist, but my experience is that they are not super successful overall. Finally, there seems to be some important voices left out of the creation of a school model based on the factory – educators! Shouldn’t their voice, their knowledge be at the table when we are trying to build a system of learning? That may be the mindset of many educators now. But in the 1900s, most educators went along with the plans set forth. Check out this quote from Ellwood P. Cubberly, an American Educator, author, and Dean of the Stanford University School of Education:

“Our schools are, in a sense, factories in which raw materials (children) are to be shaped and fashioned in order to meet the various demands of life. The specifications for manufacturing come from the demands of the twentieth century civilization, and it is the business of the school to build its pupils according to the specifications laid down.”

Ellwood P. Cubberley (1868-1941) – American Educator, author, and Dean of the Stanford University School of Education

This thinking quickly became the standard for schools and school districts. A whole new hierarchy was set up, similar in thinking to the business: decisions would flow from the state board of education down to local school boards, on to superintendents, then to principals, and finally to teachers who would, like factory workers, be expected to follow the guidance in lockstep. The students did not matter. They were no more than raw material in the formation of a more perfect industrialized workforce.

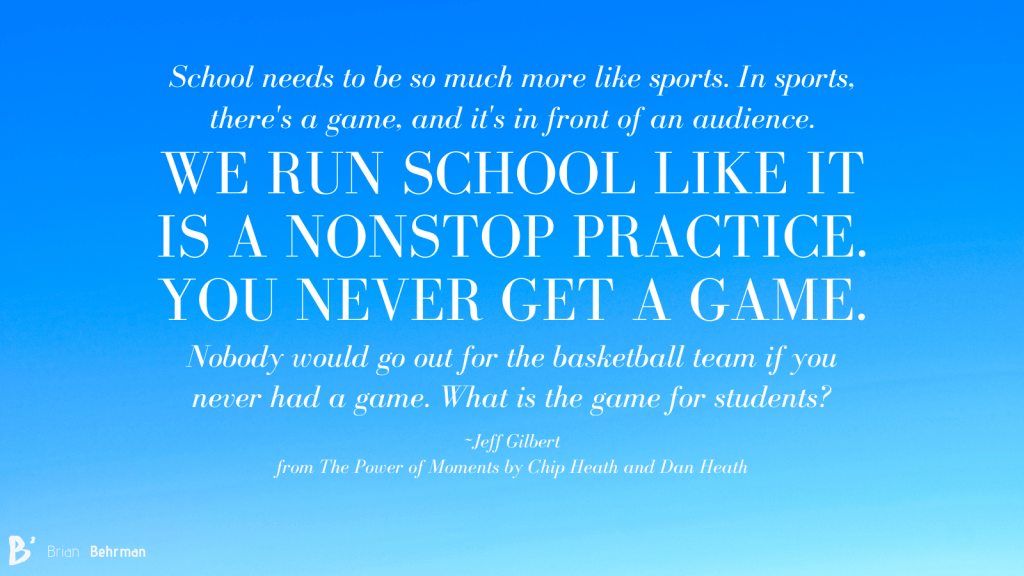

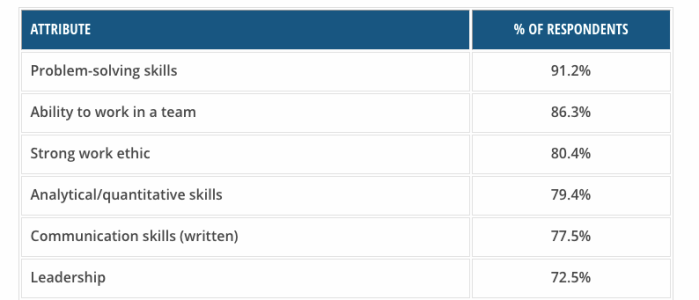

I would love to be able to say that this thinking from the 1900s has left, but I cannot. Those factory model mindsets still prevail in many school settings here in America. If you ask politicians what is needed to make education more successful, they will talk about stricter standards, better methods of evaluation of teachers, or possibly a longer school day or year. The focus, far too often, seems to be on procedures rather than results. And that brings us to the title of today’s blog. Far too much time is being spent on logistics instead of focused on learning. But when we talk to business leaders, many of them are saying that they are not able to find workers appropriately prepared for the workforce. They are telling us that the skills workers need have more to do with collaboration, teamwork, and problem solving. Check out these results from the National Association of Colleges and Employers Job Outlook Survey. These results come from the 2020 version:

Think about the conversations you have at school. If you are like me, far too often we get drawn into conversations about the organization of the schedule in the day, the length of a school day or year, the teaching of a prescribed curriculum, the size of a class, the use of a textbook, or the number of credits earned. Far too little time is spent paying attention to whether learning has occurred. And how do any of those conversations help us prepare kids for the future that business leaders say they need?

So here is the nudge – let us all take a moment to think about how we can move our conversations away from trying to identify the “one best system” and move towards a mindset of wanting to “get it right, and then make it better and better and better.”

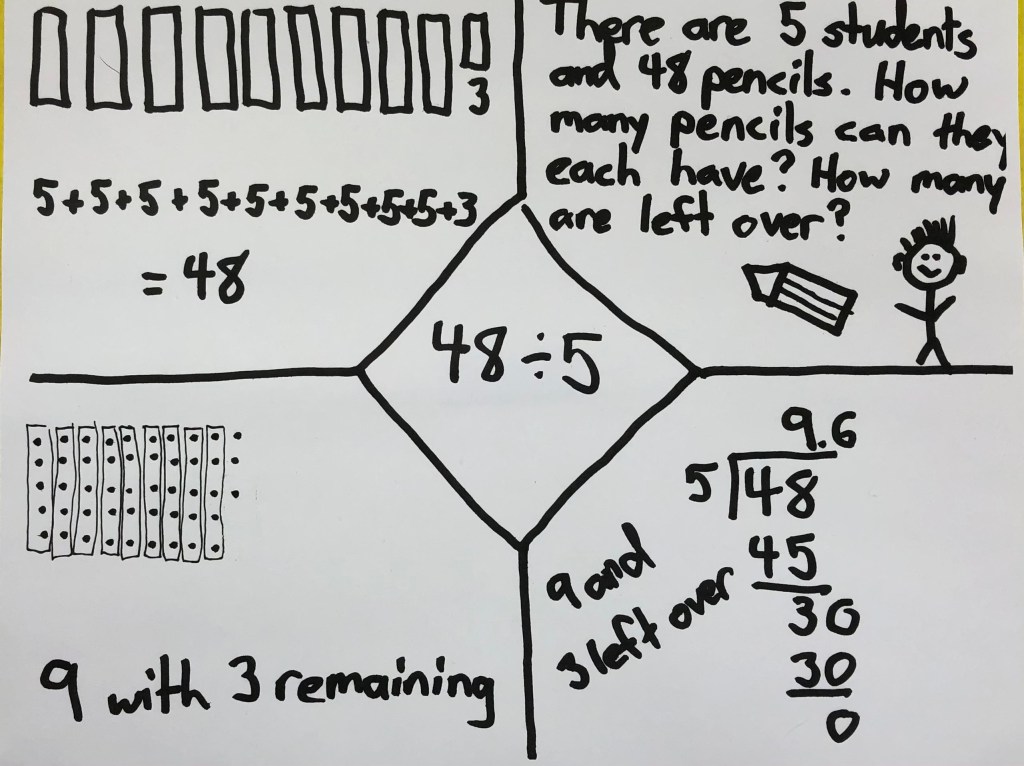

So, what might that look like? It might mean trying something totally outside the box. It might mean piloting a new strategy. It might mean utilizing supplements to your curriculum from online sources like Kahn Academy. When we analyze how kids are doing, and we really think about the results, we must recognize if the steps we are taking are impacting student learning. If the answer is no, then we must analyze what we will do to reach those kids. And if the answer is yes, then we must think about what we can do to extend that learning even further.

The reality is that the top-down factory model is not adequate for meeting the needs of our students. It is not adequate for preparing students for their future. We need to shift our goals to really invest in what we can do to get all students to master rigorous content, learn how to learn, pursue a productive level of employment, and compete in the global economy.

If you take a moment to read between the lines of what this entails, you might notice something. In our professional learning community, we have four guiding questions:

- What do we want students to know and be able to do?

- How will we know they have learned it?

- What will we do when they have not learned it?

- What will we do to extend the learning when they already know it?

I think the power to shift the system exists within each member of a school. By participating in meaningful professional learning communities, we can take that top-down approach from the factory model, and flip it on its head. We can take control of what needs to happen in our classrooms to provide support to our students.

What steps can you commit to in order to make a shift in your practice? What do you need to be able to take the next step in that shift? As Nike likes to remind us, Just Do It. Too often in education we get stuck in the planning phase, and not moving into the action phase. Act today!