Some of you may not know this about me, but many of the core memories from my pre- and teen years relate to my time as a Boy Scout. I attended weekly meetings with my troop; we had campouts throughout the year; each summer, we went to a scout camp; and every other year, there was a high adventure trip. Eventually, I worked my way up the ranks from Scout to Eagle, the highest rank available in scouting. One of the things that has to happen for a scout to advance in rank is to earn merit badges.

A merit badge is a chance for a scout to learn about things they are interested in. Topics include sports, crafts, science, trades, business, and future careers. Currently, there are more than 135 merit badges for scouts to earn. One of the most challenging merit badges I earned was the Orienteering merit badge. With that badge, we learned to use a topographic map and a compass to get from one point to the next. We learned the terrain features of the map, translated them to the environment we were in, and used that knowledge to navigate from point to point. Think of it a bit like a scavenger hunt! Orienteering comes from the word orient, which means finding your position or direction.

But Brian, what does this have to do with learning here at school? Well, recently, we started a Cluster of Professional Development around writing, with a particular focus on adding evidence and elaboration to our students’ pieces. We are engaged in this work because data has shown us that students consistently struggle with this area on our state summative assessments. Last year, only 17% of our students showed proficiency in evidence and elaboration.

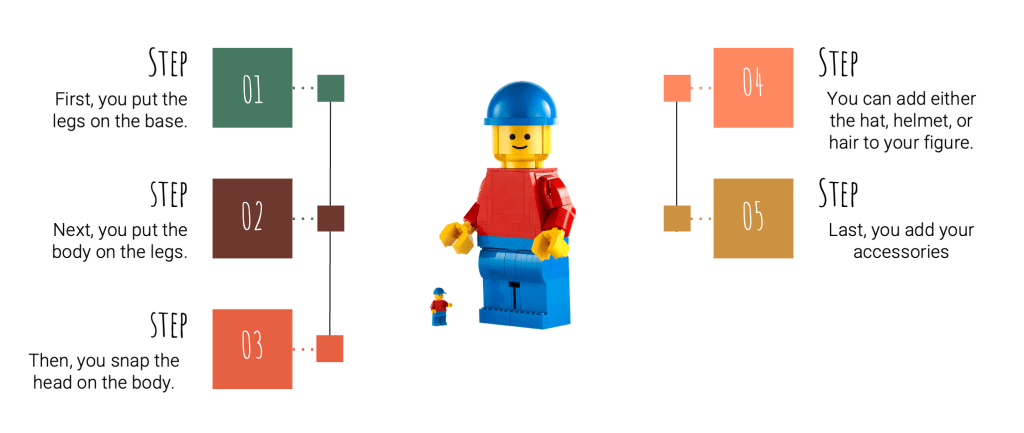

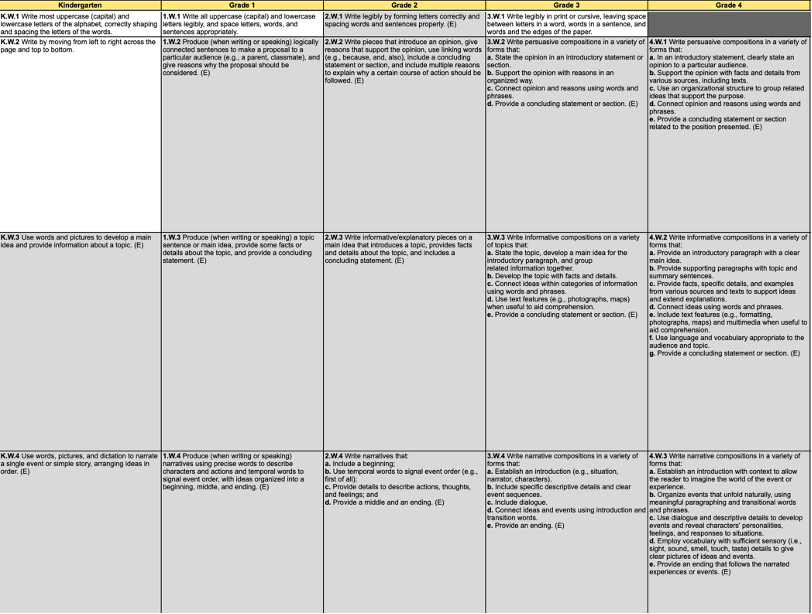

As we began planning for this professional development, one thing we did was examine our standards to truly understand where our students needed to be by the end of each grade level. For our students to reach proficiency by grades 3 or 4, steps have to be in place as foundations for learning in kindergarten, first grade, and second grade (see a recent post, The LEGO Conundrum, for more on this approach).

The analogy I’m thinking of related to orienteering is that our standards are a bit like the end point on a map. But if I took you into the woods, handed you a map and a compass, showed you where you needed to get to on the map, and gave you no other information, would you be able to orienteer your way to that location? I’m guessing that for most of us, the answer is no. Why not? We don’t know where we are starting.

I’ve been chatting with teachers about our current cluster and observing classes in writing tasks. We’re doing a great job of staying focused on where our students need to be. There’s a clear understanding of the success criteria for each grade. However, I’m starting to have concerns that we might need to work a little more on understanding where our students are right now. We need to orient ourselves to the starting point.

Just as you wouldn’t be able to orienteer your way to the endpoint on a map without knowing where you are starting, how can we hope to move our students to the standard if we don’t know where they are right now? We must orient our teaching to our students’ present levels.

You see, we (educators) do a great job of thinking about learning progressions in math. We have also grown in our knowledge of learning progressions in foundational literacy skills. But there is also a learning progression in writing skills. As a classroom teacher working to support my students’ writing growth, I must know more than just where I need to get my students. I need to start with where they are.

If we start by thinking about writing as a progression, we begin first with letter formation and handwriting fluency. Then, we work up to explicit spelling instruction. Next, we support students in building sentences, starting with simple sentences and then using sentence-building charts to add more detail to the sentence structure. From there, we progress to a basic paragraph with a topic sentence and supporting details. Then, we can use graphic organizers, color-coded paragraphs, or paragraph frames to help students in multi-paragraph writing. Over time, we slowly pull back those scaffolds for students to do these parts independently.

But here’s the thing: if I were a second-grade teacher, and I asked my students to create multi-paragraph pieces of writing when they are currently still at the simple sentence level, and I only focus on trying to get them to write multi-paragraph writing, they will break down. They will reach frustration. They will believe they are not a good writer.

In math, we meet students where they are in the progression. We must do the same for our writers. If you are looking for a great resource to support your understanding of writing progressions, check out this fantastic resource from Reading Rockets called “Looking at Writing.” You can work through the progressions, beginning with Pre-K writing through grade 3. There are writing samples, suggestions for the next steps, and ideas for instructional strategies to move students forward in their learning.

Awareness of progression is key to orienting our students toward successful growth.

What are your thoughts? How have you used progressions of learning to support student growth? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below!