This fall, The Center of Excellence in Leadership of Learning at the University of Indianapolis is offering a Science of Learning Micro-Credential. When I saw information about it over the summer, I immediately signed up. I have long been fascinated by the human brain’s learning process. That makes sense, as I was reminded in a recent professional development session, because learning is the top value I selected when reading “Dare to Lead” by Brené Brown.

This Micro-Credential has an engaging format, comprising a total of 8 asynchronous modules and 4 synchronous learning opportunities. InnerDrive, a mindset coaching company based in the United Kingdom, presents the asynchronous learning. The company works closely with education. The first module of learning focused on Cognitive Load Theory, which I have previously written about (you can find those posts here, here, and here).

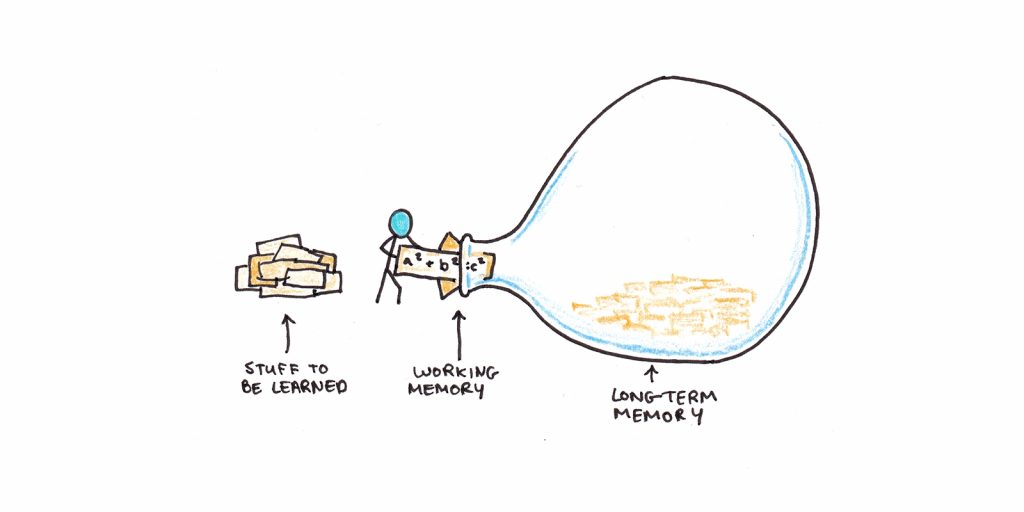

If you haven’t learned about Cognitive Load Theory, it’s based on the idea that our working memory has a limited capacity (for most people, approximately 4-7 pieces of information), while our long-term memory is very large – potentially even unlimited. During the first asynchronous module, InnerDrive presented an interview with Zach Groshell. He is a teacher, instructional coach, educational consultant, and author. I’ve referenced him and his book Just Tell Them in past posts.

He describes Cognitive Load Theory and the process of moving information from working memory to long-term memory as a bottleneck. If we define learning as creating a change in long-term memory, then our job as educators is to determine how to address that bottleneck.

Research tells us that there are several ways to address the concept of the bottleneck:

- Break learning into smaller bits: If you chunk information, you’re able to take complex ideas into smaller and more digestible steps. That might include starting with simple examples and then gradually adding complexity. Alternatively, you might use a worked example where you show step-by-step most of the problem, leaving students to complete the last portion on their own. Or you might scaffold learning by providing support like a sentence starter or graphic organizer, and you fade the scaffolds over time.

- Remember that busy does not equal learning: As I mentioned earlier, learning is about making a lasting change to long-term memory. One of the realities of education is that sometimes we focus more on what students are doing than what they are learning. Cognitive science tells us that utilizing retrieval practice, promoting connections between topics of learning, utilizing spaced practice, and creating opportunities for students to utilize self-explanation out loud or in writing.

- Success drives motivation: All humans gravitate towards assistance and support. When we feel successful in a learning environment, we strive to learn more. I don’t know about you, but I love to utilize YouTube as a learning tool. I can’t tell you how many of my YouTube searches involve fixing something. The other day, I was told that one of my brake lights had gone out on my truck. I spent about 5 minutes trying to figure out how to access the brake light, and finally pulled out my phone, watched a 30-second clip, and had the brake light replaced in under 2 minutes. Because of that success, I feel comfortable trying to learn more through a video format again. As teachers, it’s essential to find ways to help our students achieve success within the classroom setting. That maintains their motivation in the learning environment.

Understanding how the human brain learns is a key part of supporting students. We need to focus on the key points of learning. It’s what we’re here for!