At the beginning of the month, I had the privilege to attend The Reading League’s 7th Annual National Conference in Syracuse, NY. I went with several others from our district. The goal of the conference is to develop a deeper understanding of the science of reading and learn about the implications for teaching and learning. In the coming weeks/months, I look forward to sharing with you some of my key takeaways from this conference. There were several amazing presenters!

One of the first sessions I attended was led by Pamela Snow. She is a Professor of Cognitive Psychology Much of her work is centered around the early transition from language to literacy and the ways this transition is supported in the classroom. In that session, she reminded me of something that I shared in our recent PD on the Science of Reading – Human brains weren’t originally meant to be a reading brain.

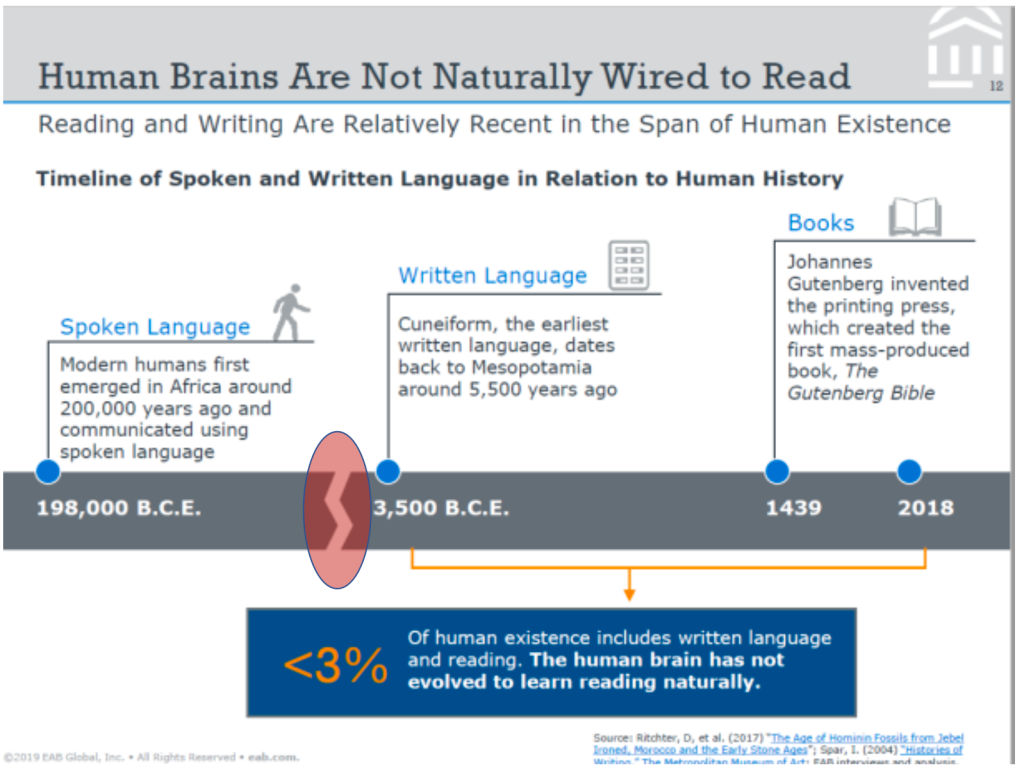

The chart below was one she shared during her presentation and served as a good reminder that less than 3% of human existence includes the use of written language.

What’s important for us to keep in mind given this information is the reminder that Language is a paradox (this theory comes directly from Pamela Snow) – “Humans have evolved a special facility for oral language, such that it is innate (biologically primary). We have a “language instinct.” However, it is highly vulnerable to a range of developmental conditions (e.g. hearing impairment, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, brain injury, or developmental language disorder). For humans, language is highly sensitive to environmental exposure.”

At times, when a reader is struggling with transitioning from an oral language structure to learning to read a written language structure, or as a student expands their reading skills beyond the oral language skills they have been exposed to, students may struggle with their reading. Literacy (reading and writing), builds upon oral language skills (vocab, speaking/conversation skills, syntax, phonological/phonemic awareness). When students lack language comprehension (remember the reading rope?), they will struggle to read fluently, which will impact their reading comprehension.

Readers with strong oral language abilities are more likely to develop strong reading abilities. Those strong reading abilities in turn will increase a reader’s vocabulary and background knowledge, which will further strengthen their reading abilities.

So what does this mean in practice? It means that our classrooms need to not only be a literacy-rich environment (lots of reading and writing), it also needs to be an oral language-rich environment (listening and speaking). Whenever possible, for all levels of readers, we can strengthen oral language skills by building opportunities for conversation, narrative discourse (think storytelling), procedural discourse (explaining a procedure), and expository discourse (informative or persuasive). Ultimately we can think of the oral language as the engine of literacy skills, while high-quality instruction in language development and reading is the fuel for success.

What are some of the ways you support oral language in your classroom? Share your thoughts and ideas in the comments below!

One thought on “The connection between oral language and reading instruction”