Over the last couple of months, my posts here have been focused on the primary purpose of reading. In the first post, I shared that in my belief, the ultimate reason we teach our students to read is so that they can learn how to comprehend text (you can see that first post here). Then over the course of that post, along with part 2 and part 3, I dug into a few of the key concepts that students need to be able to do in order to read with solid comprehension. As a reminder, the 4 key things that students need to be able to do to comprehend what they read is to:

- Read the words accurately and fluently.

- Understand the meaning of the words.

- Have adequate background knowledge.

- Focus attention on critical content.

In the first 3 posts, we dug into those first 3 concepts. Today’s post is going to primarily be thinking on how we help students to focus on critical content. Much of my thinking around these four concepts comes from a session led by Anita Archer on reading comprehension that I attended while at The Reading League National Conference in Syracuse this fall. She created a checklist for teachers to know what skills students need to so that they can accomplish each of the 4 key things listed above. Here’s the checklist related to focusing on critical content:

- Ask questions on critical content as we read books to students.

- Ask text-dependent questions as students are reading text.

- Have students generate questions on passages they read.

- Teach text features, both narrative and informative.

- Use retrieval practice procedures to review key content.

- Have students write in response to passages.

The first thing that I note as I look over this list, is that as the teacher, we must be prepared in advance with a knowledge of the text. If we want to help our students focus on critical content, we must pre-read a text so that we know what content is critical. During that pre-read, it’s a great time to mark key passages that you might want to ask a question about, and ideally plan what that question might be.

But that last bullet point that you see above regarding writing responses was reiterated in a recent blog post by Timothy Shanahan. A key point that I pulled from that post is:

So, as we are reading to our students, or as our students are reading independently, we need to be able to ask questions that guide and monitor students’ comprehension (that’s what the National Reading Panel said back in the year 2000). Ideally, those questions we ask should be text dependent – in other words, students must also provide evidence from the text to support their answers (I used to call this “Back your Smack” when I was a classroom teacher). We want to be sure that our students have read the text!

But at the same time, it is valuable for our students to develop their own questions as they are reading. They might choose to ask questions about the main character, the setting, the problem in the story and how it was solved, or what happened in the end. We want to be sure that students learn to ask questions like the ones we’d ask – in other words, they must ask questions that can only be answered if you have read the text. This could also be a great time to teach students about Depth of Knowledge – to help them learn about the different types of questions that exist, and how they might develop questions with higher levels of thinking.

But let’s get into some of what Shanahan was getting at in his post – focusing on those reading comprehension strategies that we often teach as a stand-alone skill do not always support our students in learning to comprehend what they read better. What we’re learning as more research studies are shared is that while there is “nothing wrong with asking questions about what the kids have read, just don’t expect such practice to exert much impact on the ability to deal with specific question categories, nor even to have any impact on reading comprehension.” (Shanahan, 2023).

In the quote in the graphic above, Shanahan suggests that summarizing, developing an understanding of text structure, and/or paraphrasing are much more impactful in growing student comprehension. And that makes sense to me – to do any of those things, readers are required to think deeply about a text, which is certainly going to improve reading comprehension.

So what does that mean in practice? We often talk about how readers are writers, and writers are readers. One thing you might consider implementing with your students is a protocol for writing about the text we’re reading. Not just making connections, but truly thinking about pieces of the text structure – things like the setting, who the main character is, what is the character’s problem/conflict/goal, how does the character comes to a resolution, what happened in the end of the piece, and what are the themes.

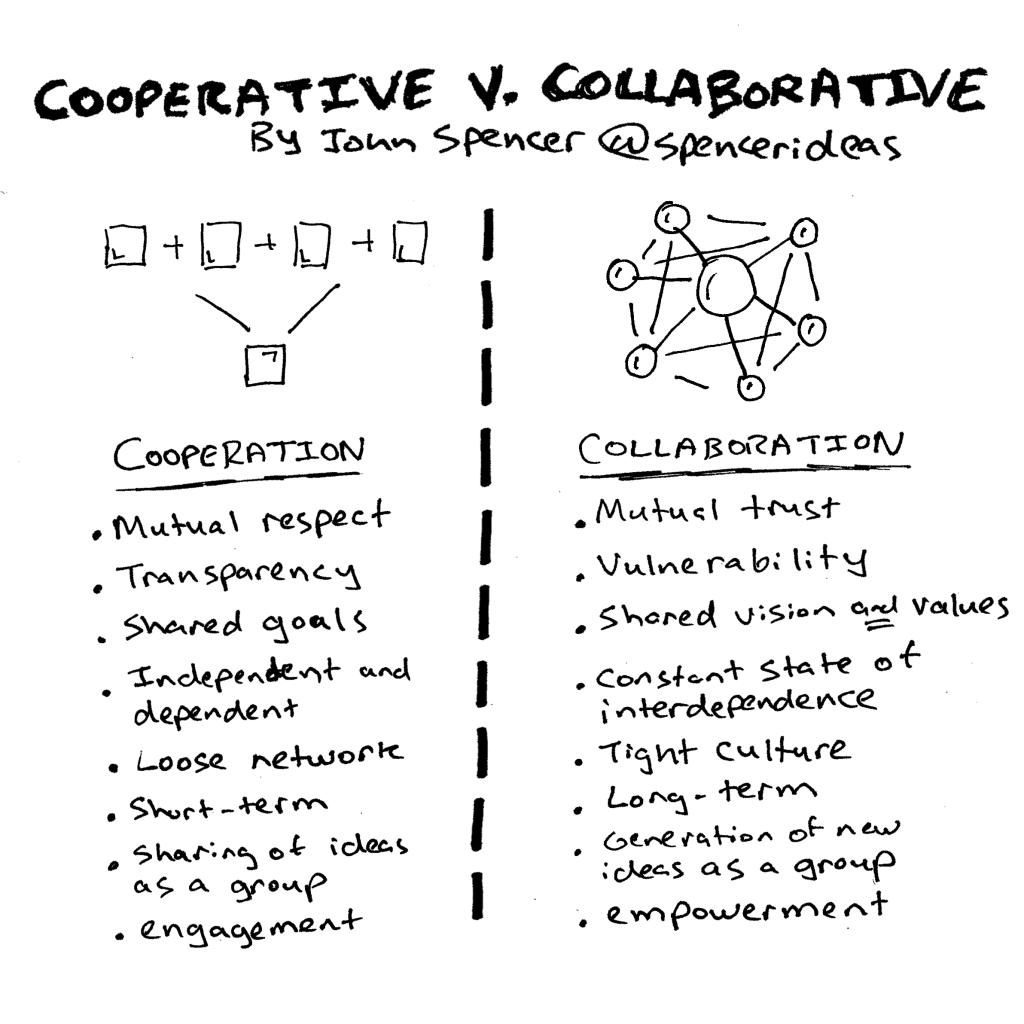

To develop these skills with students, you might start with partners doing a shared retell – maybe partner A defines the setting of the story, the main character, and the problem, while partner B shares about the beginning, middle, and end of the story and the eventual resolution of the problem. Through verbal practice, collaboration, and feedback, students will learn how to then craft their own summary. Over time, you might then work towards having students work collaboratively on developing a summary of the story. Creating a list of sentence stems might help in this process. Some ideas for what that might look like include:

The problem that exists with much of our question-and-answer strategies of stand along comprehension skills is that really, all it’s doing is testing a student’s recall of the test. This is something we’d do for an assessment, not a strategy for teaching a student how to comprehend. Through our guidance, we can help our students to analyze what it is they read. This analysis forces our students to dive back into the text, to reread, and to think deeply about what the text is really saying. These thinking skills will support comprehension much more than basic question and answer skills.

Have you ever utilized written or spoken responses in your class? How has it supported your students in developing their comprehension skills? Do you have any new ideas from what’s shared above? Let us know a bit about your thoughts in the comments below!