I’ve recently been reading the book Just Tell Them: The Power of Explanations and Explicit Teaching by Zach Groshell. I see it as something of the convergence of the work from John Sweller on Cognitive Load Theory and the work from Anita Archer on Explicit Instruction. I’ve been really enjoying the book, and I highly recommend it as a way to reflect on how you explain your instruction to your students. Plus, it’s a speedy read!

I often think of people as either novices or experts, almost as if they are binary. But what I hadn’t thought about carefully enough that Groshell calls attention to is that the transition from novice to expert really exists along a continuum. The reminder about the needs of learners based on where they are in the learning process was probably one of the greatest aha moments for me. Let’s dig into that a little bit.

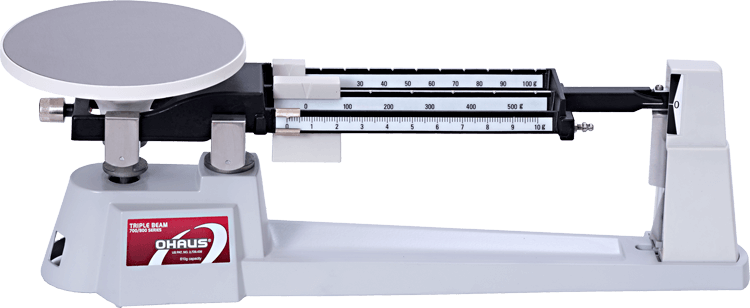

As a former science teacher, I will use an example of something that I often felt all of my students came to me as something of a novice at: using the triple beam balance to measure the mass of objects. We would learn this skill early in the year because many of the labs we would do throughout the year would require using the balance and getting accurate mass measurements. In case you’ve forgotten what a triple beam balance looks like, the ones we used in my classroom were practically identical to this:

When we learned to use the triple beam balance, I would often take one of our balances, show our students how to “zero” the balance, and then take a random object to find the mass. To build background knowledge, we’d talk about how many people had ever used a scale that you had to move the weights (when I was in the classroom, most doctor’s offices still had that type of scale, not the digital ones that are everywhere now). Then, I’d explain how the balance is similar.

To allow everyone to see the process, I’d place the balance on my document projector and use it like a camera to project the steps on the screen for all to see. First, I’d take my object and place it on the pan. Then, I’d explain that you start by moving the 100 g mass. Once it gets to the point where the balance goes down, you go back to the previous notch. Then, you move to the 10 g mass. Once the balance goes down, you go to the previous notch. Finally, you slide the 1 g marker until the balance is zeroed or the marker on the right points to the 0 mark. That would tell us that the object’s mass is the same as the mass we moved on the balance’s three beams. We would then add up the 100 g mass, the 10 g mass, and the 1 g mass rounded to the nearest tenth of a g. We’d do a couple more examples with objects I had on or around my desk. I might have students say what step to do next, but I was still moving the masses on the balance, although they could see it on the screen.

After a few samples, I’d have one member of the table group come and get a balance with a few objects on a tray to bring back to their table. Then, I’d set them free. And that is where I made my mistake. Invariably, table groups would have a hard time. One group would have an issue, so I’d have to answer those questions. While I was helping that group, other groups would have problems, but with nobody to help, learning would break down, and engagement would break down. The different groups were entirely disengaged when I finished with the first or second group. Potentially, there were behavior issues. Kids were frustrated because they “couldn’t get it.” I would see kids from across the room doing things in the wrong order but couldn’t do anything about it because I was stuck at this table helping this group.

In retrospect, I see the error of my ways. I went directly from the “I do” modeling portion of my lesson to the “You do” portion. I skipped the “We do” portion and jumped directly from the novice to the expert stage, but my students weren’t yet experts. Insert face palm emoji here!

If I could go back, I’d do the task differently. I’d still model the task in the “I do” stage the same way. Nothing seems wrong there. However, I need to strengthen the “We do” portion of the lesson. To do that, each tray would have identical objects. That way, I would know they had the same mass. This would allow me to do a completion problem, where a portion of the task is shown to them, and then they need to finish the final step to find the answer. For the triple beam balance, I’d show them (and have them follow along on their own balance) what to do with the 100 g mass, then the 10 g mass, and then have them use the 1 g mass to find the result. We’d use something like a whiteboard to write our answers, then use a “3… 2… 1… show me” to quickly check how people did. I’d be able to see if any groups were way off that needed additional support, if we were ready to pull back on support as a class, etc. Over time, I’d fade the support, adding more steps they would complete on their own, eventually getting to the point that students were working in their groups, finding the mass of objects they selected around the room, and then having me check their work.

Chances are, this process would take more than one day to play out, but by following a similar process, I’d build a stronger understanding of the task at hand. What I found in my old methods was that I often had to reteach the triple beam balance every time we used it because the methods I used never got my students to master it in the first place. By taking a little more time the first time and ensuring we all get to mastery, we might not have to spend as much time on a reteach the next time we pull out the triple beam balances.

Do you ever find that with something you teach, you have to reteach every time you come back to it? Maybe you need to rethink the gradual release of the task in your teaching to get your students to mastery in the first place.

This is a sign of our rush to get to letting the students “do the work.” And trust me, I get it! We want them to be able to do it! But what is the cost of letting them do it if they cannot do it correctly? They might practice incorrectly and solidify their understanding of an incorrect method, making your job harder to reteach. Or they might become frustrated and just start to believe “I’m not a ____ person” (fill in the blank with the appropriate subject area). By remembering this concept of the novice to expert continuum, slowly fading our support, and providing models that students can go back to, they are better able to figure it out.

My favorite suggestion from this section of Groshell’s book was the idea of a completion problem. Imagine math class with a problem that takes 4 steps to solve. In a completion problem, you model steps 1 through 3 for your students and then ask them to do step 4 on their own. After you have mastered that step, you fade the support by modeling steps 1 and 2, asking the students to do steps 3 and 4 independently. With mastery, you fade to only modeling the first step. Eventually, you get to the point where you do not complete any of the steps because your students know how to do the entire process. When we explicitly teach math (or anything), it becomes easy for our students. If you have students take pictures of these models, or you take pictures on your own and then put them on Canvas for your students, they now have a resource they can return to any time they need to remember how it’s done. I loved this idea – I often modeled problems. I frequently asked students to tell me what to do. But I never went to the level of thought that Groshell went to here. I hope it’s an aha for you too!

So, what is a takeaway for you? What might you try to do differently in your classroom due to this post? How will you think of your students a little differently now that you know about the idea of the novice to expert continuum? Share your thoughts in the comments below!