In last week’s post, I began to really dig into the concept of the purpose of reading. With our work around Science of Reading, we have really spent a lot of time, especially in our early grades, focused on structured literacy and skills like phonemic awareness, phonics, and decoding, but as Natalie Wexler reminds us:

What I was focused on in my last post (which you can see here) is digging into the idea that the ultimate purpose of reading is to comprehend the words that are on the page. At a conference I recently attended, Anita Archer shared the four things that all students must be able to do in order to comprehend:

- Read the words accurately and fluently.

- Understand the meaning of the words.

- Have adequate background knowledge.

- Focus attention on critical content.

Last week, I focused on the idea of accuracy and fluency. Today I’ll be digging into the idea of understanding words. In future posts, we’ll dig into building background knowledge and focusing on critical content.

As you know, I always love to understand the why behind what we do, so what does the research say about understanding the meaning of the words in relation to comprehension? I think we can all agree that vocabulary is related to reading comprehension. In fact:

“…one of the most eduring findings in reading research is the extent to which students’ vocabulary knowledge relates to their reading comprehension.”

~Osborn & Hiebert, 2004

I think we’d all agree that for our students to be able to read fluently, they need to know the words that they are reading. When our students don’t know the meaning of a word they are decoding during text reading, they must use context to figure out what the words mean. This added cognitive load takes away from fluency – one of the things that must be in place for solid reading comprehension.

There are several ways we can make sure that our students have that strong foundation in their vocabulary. Anita Archer suggests the following checklist to help build vocabulary:

- Use high-quality classroom language.

- Consistently use academic language.

- Read narrative and informative read-alouds in primary grades.

- Promote wide independent reading.

- Teach word learning strategies (context clues, morphemes, and resources like dictionaries, thesauruses, etc.).

- Explicitly teach critical vocabulary terms.

Over the years, I’ve spent time sharing about the work of John Hattie. His research says that vocabulary programs have an effect size of 0.67 (that’s pretty high, and definitely above the “hinge” point). In fact, Bob Marzano says:

“Direct vocabulary instruction has an impressive track record of improving students’ background knowledge and comprehension of academic content.”

So, what might a vocabulary instructional routine look like? This is the format that Archer suggests – just like with any other part of the five pillars of reading, it should be systematic and explicit. To do that, we should introduce the word, introduce the word’s meaning, illustrate the word with an example (and non-examples when it’s helpful), and then check for understanding. Let me take you through those steps a little more in-depth:

Step 1: Introduce the pronunciation of the word: You should display the word in some way, maybe on the screen, written on the board, or on chart paper. Then, read the word to the students and have students repeat it. With multi-syllabic words or more difficult words, repeat it several times. You might also have students read the word by parts, tap the word, etc.

Step 2: Present a student-friendly explanation: Tell the students an explanation, or have the students read an explanation with you. This might include using the word in a sentence, providing synonyms or antonyms, etc.

Step 3: Illustrate the word with examples: You might use concrete examples like having an object or acting the word out. You might use a visual example like an image or picture. Or you might use a verbal example to explain the word.

Step 4: Check students’ understanding: You might choose to do this in a few ways. You could ask deep processing questions, give the students think time, and then ask partner A to tell partner B. You might have students discern between examples and non-examples, so you might share a sentence and then ask students to say whether it is an example of the word or not. A third way you might check for understanding is to have students compare the vocabulary term with another term. You might have partner A share examples of ways the words are similar, and partner B share examples of ways the words are different.

Linnea Ehri tells us that if words have been read before and stored in memory, prediction strategies are not required for a reader to decode. When we can introduce difficult vocabulary words to our students in an explicit way before teaching, then our readers are better able to focus on their primary task in reading, comprehension.

What strategies have you tried in building vocabulary with your students? What has worked well? What hasn’t? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below!

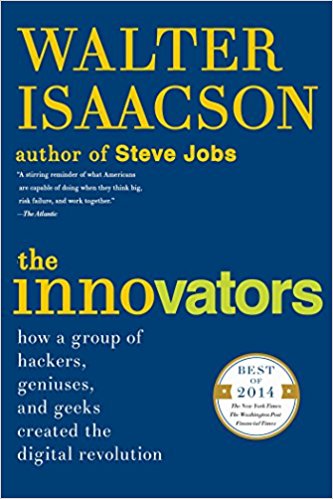

The Innovators has the subtitle “How a group of hackers, geniuses, and geeks created the digital revolution.” This book caught my attention for a couple of reasons – first, I’ve always been something of an early adopter of technology. I love to check out new and exciting innovations. A second reason that this caught my attention is that I’m always curious about how people made the leaps to take us from the earliest computers (devices that took up entire rooms in the basement of college buildings or at military bases), to the technology that I can hold in my hand every time I pick up my iPhone.

The Innovators has the subtitle “How a group of hackers, geniuses, and geeks created the digital revolution.” This book caught my attention for a couple of reasons – first, I’ve always been something of an early adopter of technology. I love to check out new and exciting innovations. A second reason that this caught my attention is that I’m always curious about how people made the leaps to take us from the earliest computers (devices that took up entire rooms in the basement of college buildings or at military bases), to the technology that I can hold in my hand every time I pick up my iPhone.