In the most recent post of the blog Teaching and Learning in HSE, Phil included a link to a short (under 2 minutes) video clip from Tom Guskey. I’ll include the link below if you didn’t watch the clip yet.

There were a couple of quotes that were intriguing to me. At the very beginning, Guskey states “Every time an assessment is given…that is an opportunity to learn.” However, he’s not talking only about an opportunity for the students to learn. He’s also talking about the assessment as an opportunity for us to learn. One of the best ways to assess the job that we are doing is on the consistent performance of our students. Don’t just look at standardized scores like the ISTEP or NWEA, look at anything that you treat as an assessment, whether formative or summative, as something that is also assessing you.

There were a couple of quotes that were intriguing to me. At the very beginning, Guskey states “Every time an assessment is given…that is an opportunity to learn.” However, he’s not talking only about an opportunity for the students to learn. He’s also talking about the assessment as an opportunity for us to learn. One of the best ways to assess the job that we are doing is on the consistent performance of our students. Don’t just look at standardized scores like the ISTEP or NWEA, look at anything that you treat as an assessment, whether formative or summative, as something that is also assessing you.

I loved the strategy that he suggests of keeping a tally of the problems that students have missed. He shares that “If every kid missed a question, that is not a kid learning problem. That is a teacher problem.”

If you are using good planning methods, with backwards planning of your units of study, and you start with the end in mind, and you get to that end and the kids missed something that you feel you taught, take a moment to reflect on how you taught that skill. The easy out is to say “the kids didn’t get it”. The much harder reflection for any of us to make is to say “maybe I didn’t do a great job of teaching this”. When that is the reflection we make, it allows us to use the assessment as a way to improve our own teaching.

As I watched this clip from Guskey, the comments about self-assessment made me think of a recent episode of the Hack Learning Podcast titled How One Simple Tool Helps Uncover Your Biases (you can follow this link to go to a page where you can listen to this episode). Hack Learning is a podcast that was created by Mark Barnes, a classroom teacher, author, and publisher of the Hack Learning Series. While the topic in this podcast is a different form of self-assessment, I feel it is worth sharing.

As I watched this clip from Guskey, the comments about self-assessment made me think of a recent episode of the Hack Learning Podcast titled How One Simple Tool Helps Uncover Your Biases (you can follow this link to go to a page where you can listen to this episode). Hack Learning is a podcast that was created by Mark Barnes, a classroom teacher, author, and publisher of the Hack Learning Series. While the topic in this podcast is a different form of self-assessment, I feel it is worth sharing.

As you know, we all have biases. If you have never taken an implicit bias test, google it and give it a shot – you might be shocked by the results. Our biases can creep into our conversations in the classroom with students. What we have to remember though is that those biases can have an impact on the learning that happens in your classroom.

In this episode of Hack Learning, Barnes shares a portion of the book Hacking Engagement by Jim Sturtevant. In the book Sturtevant shares a story from early in his teaching career where, as a world history teacher, he professed his position on what might be considered a controversial subject. He felt that the majority of the class was on board with him, there were some head nods, and they agreed. After the lesson, one student came up and said “You should be careful about promoting your views so passionately. I don’t agree with you, and I’m not alone.”

In this episode of Hack Learning, Barnes shares a portion of the book Hacking Engagement by Jim Sturtevant. In the book Sturtevant shares a story from early in his teaching career where, as a world history teacher, he professed his position on what might be considered a controversial subject. He felt that the majority of the class was on board with him, there were some head nods, and they agreed. After the lesson, one student came up and said “You should be careful about promoting your views so passionately. I don’t agree with you, and I’m not alone.”

Sturtevant’s initial reaction was that it was no big deal – this is the opinion of one student. Who cares? But as he reflected further, he came to the realization that by sharing his controversial beliefs, he was erecting barriers between himself and students. As he goes on to say in the text “Why in the world would I want to alienate certain kids who may not agree with me on an issue.”

Think about your own interactions with peers, in person or on social media. When someone expresses a bias that you don’t agree with, what do you do? You might choose to avoid that person, you might end your friendship, or you might choose to block the person on social media (this is something that I definitely saw happening on Facebook during the most recent election cycle – I saw several friends share that they had blocked or unfriended everyone who’s beliefs opposed their own). Our students will do the same things if we express our own biases, especially if they do not view things the same way as us. We might even end up alienating the families of those students as well.

So, what can we do to help us identify our biases and avoid building those barriers between ourselves and our students? What Sturtevant did was to create a Teacher Disposition Assessment (TDA). As a world history teacher, there were several aspects of his curriculum that could be seen as controversial. He identified those things that had the greatest potential to be controversial, and then created a statement from it. Here is an example of one question on his TDA:

“Muslims should be restricted from entering the United States”

- Sturtevant strongly agrees

- Sturtevant somewhat agrees

- Sturtevant somewhat disagrees

- Sturtevant strongly disagrees

- Sturtevant’s opinions on this issue are unclear

Every statement included the same five options as a response. He then took the statements and created a SurveyMonkey to be able to allow students to respond anonymously to the TDA. As he says “It’s fine to be provocative; such statements will engage your audience.” Sturtevant uses the TDA as an exit ticket at the end of the semester, but he feels that it could be used at any time of the year.

Sturtevant suggests debriefing after you receive the responses. You can share the results with your class and ask students what it says about you and their perceptions of you. He has even gone so far as to create an anonymous Google Form where students can give advice a feedback on times that biases pop up in the classroom. Finally, Sturtevant asks his students to monitor their own actions moving forward. He has found that completing the TDA has led students to think about their own actions and behaviors, and has led to some amazing in class conversations.

Talk about a strong self-assessment. Asking your students to assess your biases based on statements and action in your class – that takes some guts. But think about what that says to your students. You are telling them that you are aware of the fact that you might have some biases, and based on your results, it may even lead you to make adjustments to your own statements and actions. You are also showing them that you want to prevent the barriers that we might accidentally create when we let our biases creep into our teaching. It’s important to remember that we all have biases, and those biases can impact teaching and learning.

I’m curious if there are any out there who have had issues with biases creating barriers. Maybe it happened when you were a student and a teacher or professor said something that didn’t sit well with you. Or maybe you realized later that something you had said or done had created a barrier between you and one of your own students. If you’re willing, share your experience in the comments below.

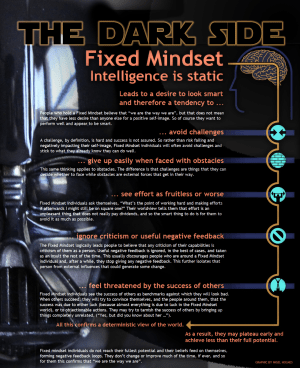

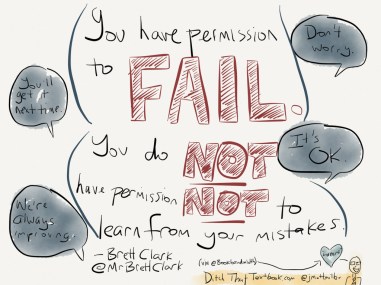

This year, as you are preparing your classroom, take a few moments to take stock of what kids will see in the hallway outside of your room, as well as when they walk into your room. Do the words on those posters have a positive connotation, or are they negative? Are they giving your students an idea of what they will be doing, or of what they will not be allowed to do? We only get one chance to make a first impression! Make sure that the impression that you make sets the students up for their best possible year!

This year, as you are preparing your classroom, take a few moments to take stock of what kids will see in the hallway outside of your room, as well as when they walk into your room. Do the words on those posters have a positive connotation, or are they negative? Are they giving your students an idea of what they will be doing, or of what they will not be allowed to do? We only get one chance to make a first impression! Make sure that the impression that you make sets the students up for their best possible year!