Earlier this week, I shared a document with the staff of my school with some strategies in dealing with students who are dysregulated. I can’t claim that I created it, it was shared with me by another administrator in the district (thanks Lisa!). I know that for some, the term dysregulation may be a new one, so let me define it quickly:

Dysregulation: An emotional response that does not fall within the conventionally accepted range of emotive responses. These emotions can be internalized by our students, which causes them to appear withdrawn, shut down, or non-engaged. For other students dysregulation will manifest as externalized behaviors such as acting out, being emotional, and trouble calming down. Some students may show a combination of internalized and externalized behaviors.

This term came to me as I began learning more about the trauma-informed school model at a training this summer with Jim Sporleder. Earlier this year I had two posts related to childhood trauma (you can find them here and here). While the strategies that we learned in our training definitely are beneficial for students who have been through trauma, we know that any student has the potential to become dysregulated, so it is important that all teachers understand how to communicate and work with a dysregulated student. At the right you will see a screenshot of the document I shared with my staff (if you click on the screenshot, it should enlarge, or feel free to download the document here: ExpectationsStudentsDysregulating).

This term came to me as I began learning more about the trauma-informed school model at a training this summer with Jim Sporleder. Earlier this year I had two posts related to childhood trauma (you can find them here and here). While the strategies that we learned in our training definitely are beneficial for students who have been through trauma, we know that any student has the potential to become dysregulated, so it is important that all teachers understand how to communicate and work with a dysregulated student. At the right you will see a screenshot of the document I shared with my staff (if you click on the screenshot, it should enlarge, or feel free to download the document here: ExpectationsStudentsDysregulating).

In the email that went with the document, I shared with our staff that working with a dysregulated student can be very difficult if we aren’t able to keep ourselves regulated. I reminded our staff of the acronym Q-TIP – Quit Taking It Personally. Logically I think we all know that when students are dysregulated, it’s not because they woke up with the goal of making the day horrible for us. There is always a lot more to the story. It’s still very easy for any of us to feel as though a dysregulated student is “doing it to us.”

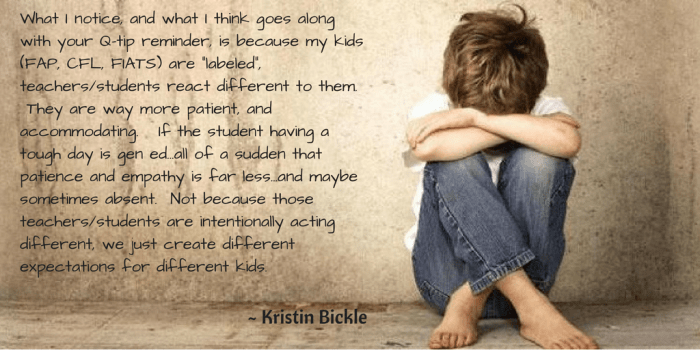

After sharing the document, I heard back from one of the Instructional Assistants that works with some of our Exceptional Learners, and her opinion about what she notices with teachers interacting with students who are struggling:

I think what Kristin says above about expectations is such an important point. We expect our students, especially for those of us who live in the middle grades, to have the appropriate responses. When they respond in ways outside those norms, we have a harder time maintaining that patience and empathy that we might be able to show students who do have a “label.”

My hope is that we can all remember that when a student is struggling, no matter what their label may be, the manifestations of that dysregulation has very little to do with us. What happens during and after the dysregulation however is something that we have control over. If we can use the suggestions in the document above, we may be able to help a student return to a regulated state, which in turn will allow us to move forward in learning and growing.

What are your thoughts of the document above? Are there strategies that have been successful for you in working with dysregulated students, that aren’t included in this list? Have you found that there are things on this document that don’t work? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Eventually, Dr. Harris learned from a colleague of a study called the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACEs Study). This ongoing study is a collaboration of Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. I believe that every educator needs to be aware of the ACEs Study. The study shows a correlation between ACEs that occurred prior to reaching the age of 18 and many health and social problems as an adult. Here are some basic stats from the ACEs Study:

Eventually, Dr. Harris learned from a colleague of a study called the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACEs Study). This ongoing study is a collaboration of Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. I believe that every educator needs to be aware of the ACEs Study. The study shows a correlation between ACEs that occurred prior to reaching the age of 18 and many health and social problems as an adult. Here are some basic stats from the ACEs Study: Why does this happen? For the normally developed brain, when it encounters a stressful situation the adrenal gland kicks in and releases adrenaline and cortisol, which gets the body ready for fight, flight, or freeze. For a child living in trauma, those adrenal glands are constantly being triggered, which causes their brain to have bottom up control, and prevents the upper part of the brain (those that control reasoning, self-control, learning, and understanding), from being able to take control. And what are the triggers for our trauma students? You may never know. It could be walking into their home, it could be a loud voice, it could be a simple as a facial expression. These triggers are so frequent that the trauma brain is constantly in fight, flight, or freeze mode.

Why does this happen? For the normally developed brain, when it encounters a stressful situation the adrenal gland kicks in and releases adrenaline and cortisol, which gets the body ready for fight, flight, or freeze. For a child living in trauma, those adrenal glands are constantly being triggered, which causes their brain to have bottom up control, and prevents the upper part of the brain (those that control reasoning, self-control, learning, and understanding), from being able to take control. And what are the triggers for our trauma students? You may never know. It could be walking into their home, it could be a loud voice, it could be a simple as a facial expression. These triggers are so frequent that the trauma brain is constantly in fight, flight, or freeze mode. In their book The Trauma-Informed School, Jim Sporleder and Heather T. Forbes identified a few strategies that we can all use to interact with students (and I would suggest that these strategies work for all kids, not just those who have been through trauma). Here’s a few of them:

In their book The Trauma-Informed School, Jim Sporleder and Heather T. Forbes identified a few strategies that we can all use to interact with students (and I would suggest that these strategies work for all kids, not just those who have been through trauma). Here’s a few of them: